昨日鲍威尔在美联储倾听(Fed listen)上致开幕词,说了过去和未来的货币政策框架以及修订方法,整体释放了短鸽长鹰的信号。全文和译文如下:

Good morning. I am pleased to welcome everyone here today. Thomas Laubach's research and support of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) helped us better understand monetary policy, and it is fitting that this work will continue today in his name. Thank you to the authors of the papers, to the discussants, and to our panel participants. Thank you also to Trevor and his team for organizing this conference; a lot of work went into bringing us together.

As in our last review, the 2025 review consists of three key elements: this conference, Fed Listens events at Reserve Banks around the country, and policymaker discussions and deliberations, supported by staff analysis, at a series of FOMC meetings. In the current review we will reconsider aspects of our strategic framework in light of the experience of the last five years. We will also consider possible enhancements to the Committee's policy communication tools, regarding forecasts, uncertainty, and risks.

早上好。我很高兴今天能在此欢迎大家。托马斯·劳巴赫对联邦公开市场委员会(FOMC)的研究与支持,助力我们深化了对货币政策的理解,今日以他的名义延续这项工作,恰如其分。感谢论文作者、评论人以及各位小组成员的参与。同时,也要感谢特雷弗及其团队为组织此次会议所付出的辛勤努力。

同上一次审查一样,2025年的审查由三个关键部分组成:本次会议、在各地储备银行举办的“美联储倾听”活动,以及在一系列FOMC会议上由工作人员分析支撑的政策制定者的讨论与审议。本次审查将基于过去五年的经验,重新审视我们战略框架的某些方面。同时,我们还将考虑可能增强委员会政策沟通工具的改进措施,涉及预测、不确定性和风险等方面。

The Consensus Statement

In 2012, the FOMC first codified our monetary policy framework in a document entitled the Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we refer to as the consensus statement. The language in the opening paragraph, which has never changed, articulates our commitment to fulfilling our congressional mandate and to explaining clearly what we are doing and why .

That clarity reduces uncertainty, improves the effectiveness of our policy, and enhances transparency and accountability.

As Chair, Ben Bernanke led the Committee through the creation of that initial consensus statement, adopting a 2 percent inflation target, and outlining our approach to achieving our congressionally assigned dual mandate. The framework laid out in that document broadly aligned with best practices for a flexible inflation-targeting central bank.

The structure of the economy evolves over time, and monetary policymakers' strategies, tools, and communications need to evolve with it. The challenges presented by the Great Depression differ from those of the Great Inflation and the Great Moderation, which in turn differ from the ones we face today. A framework should be robust to a broad range of conditions, but also needs to be updated periodically as the economy and our understanding of it evolve.

2012年,联邦公开市场委员会(FOMC)首次以一份名为《长期目标和货币政策战略声明》(我们称之为共识声明)的文件,明确了我们的货币政策框架。该声明开篇的措辞自发布以来从未更改,清晰地表明了我们践行国会赋予的使命,以及清楚阐释我们行动及原因的承诺。

这种清晰性降低了不确定性,提高了我们政策的效力,并增强了透明度和问责性。

当时,由本·伯南克担任主席,带领委员会制定了最初的共识声明,确立了2%的通胀目标,并阐述了我们实现国会赋予的双重使命的方法。该文件所规划的框架,总体上与灵活通胀目标制央行的最佳实践相一致。

经济结构会随着时间而演变,货币政策制定者的策略、工具和沟通方式也须与时俱进。大萧条、大通胀和大缓和时期的挑战各不相同,而我们如今面临的挑战又有所不同。一个框架既需在广泛的条件下保持稳健性,也需随着经济及我们对其认知的发展而定期更新。

2019–20 Review

From 2012 to 2018, the FOMC voted at each January meeting to reaffirm the consensus statement, in most years without substantive changes. In 2019, we changed that practice, conducting our first-ever public review, and said that we would repeat such reviews at roughly five-year intervals. There is nothing magic about a five-year pace. We believe that frequency is appropriate to reassess structural features of the economy and to engage with the public, practitioners, and academics on the performance of our framework. Several of our global peers have adopted similar approaches to their framework reviews.

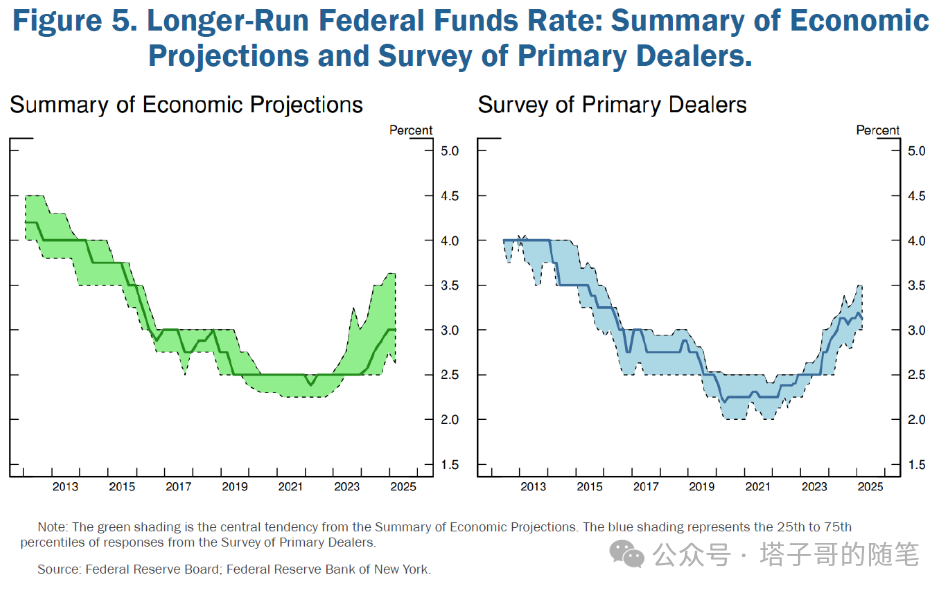

At the time of the last review, we had been living for about a decade in a new normal characterized by proximity to the effective lower bound, with low interest rates, low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve. If I could capture that era with one statistic, it would be that the policy rate had been stuck at the lower bound for seven long years following the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in late 2008 .

After liftoff in December 2015, we were able to raise the policy rate only very gradually over a period of three years to a peak of just 2.4 percent. Seven months later, we began reducing it, leaving the rate at 1.6 percent in late 2019, where it would be when the pandemic arrived a few months later. Policy rates in other major advanced economies were even lower, in many cases below zero, and in all such economies, inflation regularly ran below its target.

The sense at that time was that when the economy next experienced even a mild downturn, we would be right back at the lower bound, probably for another extended period. The post–financial crisis decade had demonstrated the pain that could bring. Inflation would likely decline in a weak economy, raising real interest rates as nominal rates are pinned at zero. Higher real rates would further weigh on job growth and reinforce the downward pressure on inflation and inflation expectations.

Reflecting these concerns, we adopted a policy to make up for persistent shortfalls from the inflation target, an approach that was common in the extensive literature on the risks associated with the lower bound. Given the downside risks to employment and inflation from proximity to the lower bound and the need to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at 2 percent, we said that following periods in which inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, we would likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

We also concluded that policy decisions would be informed by assessments of "shortfalls" rather than "deviations" from maximum employment. The change to shortfalls was not a commitment to permanently forswear preemption or to ignore labor market tightness. Rather, it signaled that apparent labor market tightness would not, in isolation, be enough to trigger a policy response, unless the Committee believed that, if left unchecked, it would lead to unwelcome inflationary pressure.

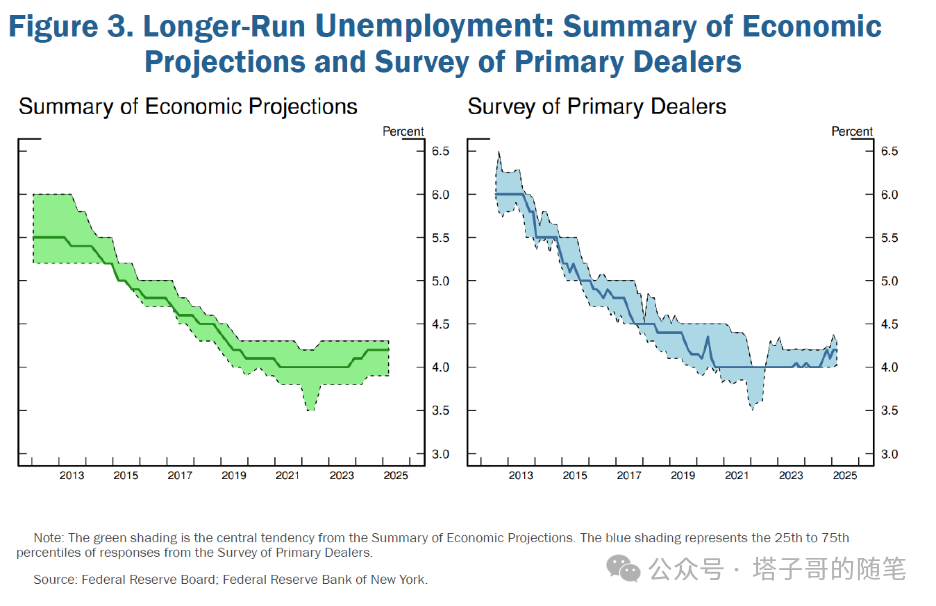

This change reflected our experience with long expansions that featured historically low unemployment amid low and stable inflation, suggesting that a policy approach that carefully probed for the maximum level of employment could bring about the benefits of a strong labor market without risking price stability. In the years just prior to the pandemic, for example, unemployment was at multidecade lows while inflation ran below 2 percent. By December 2019, estimates of the longer-run unemployment rate had fallen sharply .

The use of "shortfalls" acknowledged that a combination of low inflation and low unemployment does not necessarily pose an adverse tradeoff for monetary policy.

The economic conditions that brought us close to the lower bound and drove the changes in our consensus statement were thought to be rooted in slow-moving global factors that were likely to persist for an extended period—at least until our next five-year review. And that might well have been the case had the pandemic not intervened.

The idea of an intentional, moderate overshoot proved irrelevant to our policy discussions and has remained so through today. There was nothing intentional or moderate about the inflation that arrived a few months after we announced our changes to the consensus statement. I acknowledged as much publicly in 2021.We fell back on the rest of the framework, which called for traditional inflation targeting.

Through the end of 2021, FOMC participants continued to forecast that inflation was likely to subside fairly quickly in 2022, with only a moderate increase in our policy rate. That projection was consistent with other central banks with different frameworks and the vast majority of forecasters .

When the evidence showed otherwise, we hiked 525 basis points over a period of 16 months. The most recent data suggest that 12-month PCE (personal consumption expenditures) inflation was 2.2 percent in April, far below its 7.2 percent peak in 2022. In a welcome and historically unusual result, this disinflation has come without the sharp increase in unemployment that has often accompanied a campaign of rate hikes to reduce inflation.

The economic environment has changed significantly since 2020, and our review will reflect our assessment of those changes. Longer-term interest rates are a good deal higher now, driven largely by real rates given the stability of longer-term inflation expectations. Many estimates of the longer-run level of the policy rate have risen, including those in the Summary of Economic Projections .

Higher real rates may also reflect the possibility that inflation could be more volatile going forward than in the inter-crisis period of the 2010s. We may be entering a period of more frequent, and potentially more persistent, supply shocks—a difficult challenge for the economy and for central banks.

While our policy rate is currently well above the lower bound, in recent decades we have cut the rate by about 500 basis points when the economy is in recession. Although getting stuck at the lower bound is no longer the base case, it is only prudent that the framework continue to address that risk.

While the framework must evolve, some elements of it are timeless. Policymakers emerged from the Great Inflation with a clear understanding that it was essential to anchor inflation expectations at an appropriately low level. During the Great Moderation, well-anchored inflation expectations allowed us to provide policy support to employment without risking destabilizing inflation. Since the Great Inflation, the U.S. economy has had three of its four longest expansions on record. Anchored expectations played a key role in facilitating these expansions. More recently, without that anchor, it would not have been possible to achieve a roughly 5 percentage point disinflation without a spike in unemployment.

Keeping longer-run inflation expectations anchored was a driving force behind establishing the 2 percent target in the 2012 framework. Maintaining that anchor was a major consideration behind the changes in 2020. Anchored expectations are critical to everything we do, and we remain fully committed to the 2 percent target today.

2012年至2018年期间,联邦公开市场委员会(FOMC)每年一月的会议上均投票重申了共识声明,多数年份未作实质性修改。2019年,我们改变了这一做法,进行了首次公开审查,并表示将大约每五年重复进行此类审查。五年一次的审查节奏并无特殊之处。我们认为这样的频率适中,既可重新评估经济的结构性特征,又能与公众、从业者及学者就我们框架的表现进行交流。我们的多个全球同行也采取了类似的框架审查方式。

在上次审查时,我们正处于一个由接近有效下限、低利率、低增长、低通胀以及菲利普斯曲线极为平坦所定义的新常态中已有约十年。若要用一个统计数字来概括那个时代,那就是在2008年全球金融危机爆发后的七年里,政策利率一直被钉在下限。

2015年12月启动加息后,在三年的时间里,我们仅能逐步将政策利率提升至最高2.4%的峰值。七个月后,我们开始降息,到2019年末,政策利率降至1.6%,而几个月后疫情便接踵而至。其他主要发达经济体的政策利率更低,许多情况下甚至低于零,在所有这些经济体中,通胀常常低于目标水平。

当时的普遍看法是,当下一次经济出现哪怕只是轻微的衰退时,我们又将回到下限,可能又会持续相当长的一段时间。后金融危机的十年已经展示了这种情况可能带来的痛苦。在疲弱的经济环境中,通胀可能下降,而由于名义利率被钉在零,实际利率上升。更高的实际利率会进一步拖累就业增长,并加剧对通胀和通胀预期的下行压力。

基于这些担忧,我们采用了一项政策,以弥补通胀持续低于目标的缺口。这种方法常见于关于下限风险的广泛文献中。鉴于接近下限对就业和通胀的下行风险,以及将长期通胀预期锚定在2%的需要,我们表示,在通胀持续低于2%的时期之后,我们可能会在一段时间内致力于实现适度高于2%的通胀。

我们还得出结论,政策决策将基于对“就业缺口”而非“就业偏离”的评估。这种措辞的改变并非意味着我们永久放弃预防性加息或忽视劳动力市场的紧张状况。相反,它表明,仅凭表面的劳动力市场紧张,将不足以单独触发政策反应,除非委员会认为,如果不加以控制,这种情况将导致不受欢迎的通胀压力。

这种改变反映了我们的经验,即在长期扩张中,即使在通胀低迷且稳定的环境下,失业率也能历史性地保持低位,这表明一种谨慎探求就业最大值的政策方法可以在不牺牲价格稳定的情况下,收获强劲劳动力市场的益处。例如在疫情前几年,失业率已降至数十年来的低点,而通胀却低于2%。到2019年12月,长期失业率的估计值已大幅下降。

采用“就业缺口”的表述,承认了低通胀与低失业率的组合并不必然构成对货币政策的不利权衡。

我们当时认为,促使我们接近下限并推动共识声明变更的经济状况,可能根植于缓慢变化的全球因素,这些因素预计会在相当长的一段时间内持续存在——至少直到下一次五年审查。而要不是疫情的干预,这种情况很可能确实会发生。

关于有意的、适度通胀超调的想法,在我们宣布共识声明变更后的政策讨论中变得无关紧要,并一直如此至今。在我们宣布共识声明变更后的几个月内出现的通胀,并无任何刻意或适度可言。我在2021年公开承认了这一点。我们回到了其余框架上,该框架要求以传统的通胀目标为导向。

截至2021年底,FOMC参与者继续预测通胀很可能在2022年迅速回落,仅需适度提高我们的政策利率。在与其他不同框架的央行以及大多数预测者的预测一致。

当证据显示情况并非如此时,我们在16个月内累计加息525个基点。最新数据显示,2023年4月的12个月核心PCE(个人消费支出)通胀率为2.2%,远低于2022年7.2%的峰值。这一去通胀进程在历史上颇为罕见且令人欣慰,它并未伴随着通常伴随加息以抑制通胀的失业率急剧上升。

自2020年以来,经济环境已发生显著变化,我们的审查将反映我们对这些变化的评估。长期利率目前显著上升,这在很大程度上是由实际利率推动的,因为长期通胀预期保持稳定。许多对政策利率长期水平的估计已上升,包括经济预测摘要中的估计。

较高的实际利率也可能反映了未来通胀可能比2010年代危机间期更易波动的可能性。我们可能正进入一个供应冲击更频繁、且可能更持续的时期——这对经济和央行来说是一个艰难的挑战。

尽管我们的政策利率目前远高于下限,但在过去几十年中,当经济陷入衰退时,我们通常会将利率下调约500个基点。虽然陷入下限已不再是基本情况,但谨慎起见,框架仍需继续应对这一风险。

尽管框架必须与时俱进,但其中一些元素是永恒的。大通胀之后,政策制定者们明确了锚定通胀预期的重要性。在大缓和时期,稳定的通胀预期使我们能够在不引发不稳定通胀的情况下,为就业提供政策支持。自大通胀以来,美国经济经历了三次最长的扩张期,而锚定的预期在推动这些扩张方面发挥了关键作用。最近,若非有此锚定,我们不可能在不引发失业率急剧上升的情况下实现近五个百分点的去通胀。

锚定长期通胀预期是2012年框架中设定2%通胀目标的驱动力。维持这一锚定是2020年变更的主要考虑因素。锚定的预期对我们的工作至关重要,我们今天仍完全致力于2%的目标。

2025 Review

In the current review, the Committee is engaged in discussions about what we have learned from the experience of the past five years. We plan to complete consideration of specific changes to the consensus statement in coming months. We are paying particular attention to the 2020 changes as we consider discrete but important updates reflecting what we have learned about the economy, and the way those changes were interpreted by the public. In our discussions so far, participants have indicated that they thought it would be appropriate to reconsider the language around shortfalls. And at our meeting last week, we had a similar take on average inflation targeting. We will ensure that our new consensus statement is robust to a wide range of economic environments and developments.

In addition to revising the consensus statement, we will also consider potential enhancements to our formal policy communications, particularly regarding the role of forecasts and uncertainty. As we have been reviewing assessments of the 2020 framework and of policy decisions in recent years, a common observation is the need for clear communications as complex events unfold. While academics and market participants generally have viewed the FOMC's communications as effective, there is always room for improvement. Indeed, clear communication is an issue even in relatively placid times. A critical question is how to foster a broader understanding of the uncertainty that the economy generally faces. In periods with larger, more frequent, or more disparate shocks, effective communication requires that we convey the uncertainty that surrounds our understanding of the economy and the outlook. We will examine ways to improve along that dimension as we move forward.

Let me end by saying thank you again for being here. We have been looking forward to the conversations that will occur over the next two days. These discussions will help broaden and deepen our thinking about these issues, and they are critical to the success of these reviews.

在当前的审查中,委员会正在讨论我们从过去五年的经验中学到了什么。我们计划在未来几个月内完成对共识声明具体变更的审议工作。我们特别关注2020年的变更,因为我们在考虑离散但重要的更新,这些更新反映了我们对经济的了解,以及公众对这些变更的解读方式。在我们迄今的讨论中,与会者表示,他们认为重新考虑有关“就业缺口”的措辞是合适的。而在我们上周的会议上,我们对平均通胀目标制也有类似的见解。我们将确保新的共识声明能够适用于广泛多样的经济环境和发展变化。

除了修订共识声明外,我们还将考虑对我们正式的政策沟通进行潜在增强,特别是关于预测和不确定性的作用。在审查对2020年框架及近年来政策决策的评估时,一个普遍的观察是,在复杂事件展开时,清晰的沟通尤为必要。尽管学者和市场参与者普遍认为FOMC的沟通是有效的,但总有改进的空间。实际上,即使在相对平静的时期,清晰的沟通也是一个问题。一个关键问题是,如何促进人们对经济通常面临的不确定性的更广泛理解。在冲击更大、更频繁或更不寻常的时期,有效的沟通要求我们传达出我们对经济和展望理解周围的不确定性。我们将在这方面进行改进,以推进我们的工作。

最后,请允许我再次感谢大家的参与。我们期待着未来两天将进行的讨论。这些讨论将有助于拓宽和加深我们对这些问题的思考,对于审查的成功至关重要。

总结:本次货币政策框架审查和变化符合笔者之前预期:删除平均通胀目标,从更关注就业变成双重使命,以及不再担忧通缩等。具体情况会在杰克逊霍尔上公布,美联储实际上默许了通胀略高于2%的情况,而不是机械地追求2%并且要到那个时候才开始继续宽松。

更多外资报告,产业调研,数据点评等已经发在社群里,欢迎扫码进入。

精彩评论