Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, according to Milton Friedman. It’s also a massively subjective experience.

People might have different impressions of inflation depending on their own personal ‘baskets’ of recurrent items, but they can also have different concerns based on their personal history with price pressures. Those who lived through the 1970s, for instance, might be far more inclined to seeWeimar-esque hyperinflationlurking around the corner, while those who’ve never witnessed inflation hit 2% are far more sanguine.

As Ulrike Malmendierand Stefan Nagelput it in their seminal 2016 paper examining how people actually form inflation expectations:

“Such learning from experience carries two central implications. First, expectations are history-dependent. Cohorts that have lived through periods of high inflation for a substantial amount of time have higher inflation expectations than individuals who have mostly experienced low inflation.

Second, beliefs are heterogeneous. Young individuals place more weight on recent data than older individuals since recent experiences make up a larger part of their life-times so far. As a result, different generations tend to disagree about the future.”

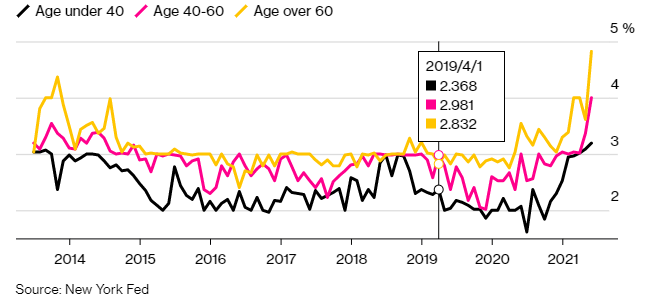

That dynamic is now fully apparent, according to data from the New York Fed, with a schism now developing between younger survey respondents who expect inflation to hit 3.19% in a year, and an older generation who sees it getting close to 5% within the same time period.

So while respondents across the spectrum of ages do see inflation trending higher, the olds expect a much higher rate than the youngs.

Median one-year ahead expected inflation rate by age group

It’s also worth mentioning that Malmendier’slatest workfocuses on central bankers’ own history with inflation, concluding that “personal lifetime experiences significantly affect the inflation forecasts, voting behavior, tone of speeches, and federal funds target rate decisions of FOMC members.”