Watch this measure of the long-term unemployed

The hottest question in Washington these days is how much more America should spend on recovery, and it’s a classic data Rorschach test. Some stare at the falling unemployment numbers and see an economy well on its way to normal. Others worry they’re not falling fast enough and fear that lingering scars will hurt long-term growth.

In fact, both groups may be right. The near-term recovery looks quite strong, especially if another stimulus package extends enhanced unemployment benefits into the fall. And the stock market certainly senses that a glorious summer is coming into view.

But as companies take advantage of the shock to introduce cost-saving technologies and as consumers emerge from lockdowns with new habits, the same old jobs won’t all be there to fill. The crisis will leave more people settling for lower wages or dropping out of the labor force altogether, and it will take more than throwing money at the problem to heal the economic wounds.

As shocking as the COVID-19 pandemic was for last year’s economy, the world’s synchronized policy response was even more surprising. Central banks cut rates, finance ministries cut checks and an astonishing effort to find a vaccine has now delivered several highly effective options.

With all that money sloshing around the world, how can we not expect a sharp rebound? Even the seers at the European Commission upgraded economic forecasts last week, following a trend set by their counterparts at the International Monetary Fund and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

U.S. unemployment has more than halved from its 14.7% peak last March, while household savings are healthy and debts are low. Poorer households even report slightly higher incomes with that extra government support. Larger firms are awash in cash and banks have plenty of capacity to lend. As winter turns to spring, Americans are managing their cabin fever with plans for shopping sprees and exotic travel just as soon as they get that second shot.

Ka-BOOM!

Our central scenario is for a steady recovery this year, with another stimulus package that will boost growth above the Congressional Budget Office’s fresh 3.7% forecast. Unemployment should drift lower from the current 6.3% rate, but it’s going to be tough going because the details in the labor data show something far more worrying.

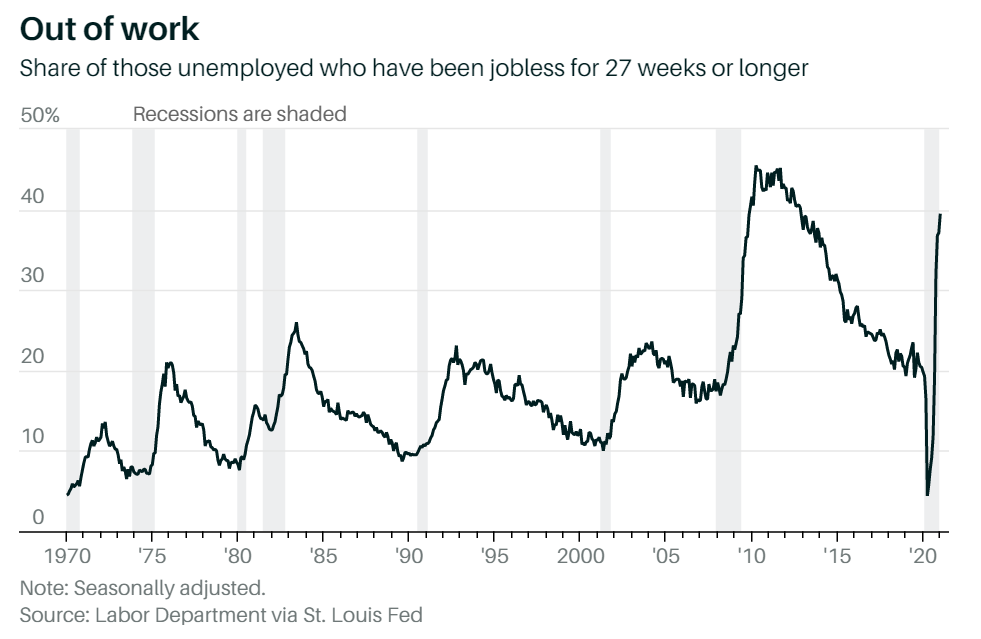

Specifically, the long-term unemployment rate, which counts those Americans who have been out of work for more than 27 weeks, continues to rise in absolute terms and as a percentage of the overall unemployed. The labor participation rate has also taken a sharp spike lower, after just starting to recover following the global financial crisis.

Many of these lost jobs may indeed re-appear when all those people head back to the mall. But many of these trends are part of a story that stretches back to the 1960s when men aged 25-54 (so-called “prime age”) began falling out of the workforce because of a complex brew of forces that included global competition, technological innovation and weakening labor unions. Some of these trends were only just improving when the crisis hit.

Meanwhile, we are only just beginning to understand the shock delivered to working women. Even as the recovery takes hold, some 80% of those who left the workforce in January were female.

All recessions aggravate the mismatch between the jobs and the jobless, but this one may be worse. When crisis strikes, companies often add new technologies to cut operating costs. This time, though, there will be further disruption from new post-pandemic consumer patterns and preferences.

When the recovery comes, as a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York points out, the new jobs won’t fit the skill sets of those who were let go. It’s not that a flight attendant can’t get land work at an online retailer’s logistics center, but it’s hardly automatic or comfortable.

And, it’s not just a question of training. If their former employer doesn’t call them back to work as demand recovers, the hunt will be even longer. If the former employer went bankrupt, it’s even harder.By one measure, nearly a third of small businesses have closed since last January.

These are not issues that can be addressed easily even with another stimulus package. The long-term unemployed, in particular, need support that is sufficient without undercutting incentives to return to the workforce, as economist Marco Annunziata points out. Progress will require investment in training and education, too, and may take a long time to deliver results.

For investors, the “good news,” if you want to call it that, is that these are long-standing trends that won’t likely undercut near-term market returns. The bad news is that by many measures, America’s workforce continues to deteriorate with all sorts of implications for long-term growth, let alone political stability.